QUADRATIC RELATIVITY FIELD DYNAMICS: MODELING HUMAN PERFORMANCE STATES

By Scott Ford

Abstract

Quadratic Relativity Field dynamics introduces and comprehensive way to model the interior and exterior differences between the normal and peak performance states of athletes as these performance states are co-created with and within the spatiotemporal relativity fields of the athletic environment.

The differences between the normal and peak performance states are seen in the radical opposition of their quadrants, while the relativity field dynamics of each performance state define exactly how these opposing states are co-created by the athlete.

Definitions

Quadratic Relativity Fields – QRFs – are a combination of the Quadrants (Q), found in Ken Wilber’s AQAL Theory, and Relativity Fields as seen in the Scott Ford’s Parallel Mode Process. For further information on AQAL see www.kenwilber.com, and for more information on Relativity Fields see www.tennisinthezone.com.

What QRFs have to do with modeling human performance begins with a description of relativity fields, or R-fields, and how they are part and parcel of every sport we play, indeed, every performance experience we have as human beings both on the field of competition and off.

Relativity Fields and Performance

A little history will be helpful. In 1978 I did something on the tennis court that immediately and consistently put me “in the zone.” The zone being the colloquial term used in tennis and many other sports to describe the peak or ideal performance state, a state of flow, but by whatever name it’s called, what I was doing on the court was putting me in the zone every time I did it, and I found that it worked for other players as well, no matter what their skill level, age, gender, or cultural background. When other players did this simple thing I was doing, they, too, immediately and consistently shifted into their peak performance state. And it never failed. To this day, this process that I’ve dubbed “The Parallel Mode Process” or PMP for short, has never failed to get players in the zone when they make a few fundamental changes in the way they use their visual and mental focus on the court.

For a more complete description of these required changes, see the above mentioned website, but the short version goes like this: what I did that shifted me from playing in the norm to playing in the zone had to do with the different way I was using my eyes on the court. The difference was that I stopped trying to keep the ball in focus as it flew back and forth across the net and, instead, fixed my focus on my contact zone, the area of open space just in front of me on the court. With my eyes focused on my contact zone, all I did was let the ball move into focus as it came toward my contact zone and move out of focus after I hit it. In other words, with my visual focus fixed on my contact zone, the oncoming ball was out of focus when my opponent hit it, but as it came towards my contact zone, it also came into clearer focus, making the creation of positive contact much easier and more consistent.

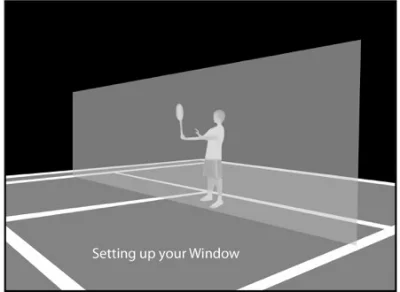

To make this visual switch, I played a childlike game of visualizing a big, imaginary window a few feet in front of me, spanning the width of the court from sideline to sideline and reaching up from the surface of the court to the height I could reach my racquet. It looked like this:

Importantly, the imaginary game I played had nothing to do with hitting the ball back across the net and into the court, but rather it involved using my racquet to keep every oncoming ball from getting past my imaginary window. When I was successful and made contact at my window, I said “yes,” but when the ball broke through my imaginary window and my contact was late, I said “no.” That was it. Nothing more; nothing less. Defend my imaginary window and use immediate yes/no verbal feedback. A simple game that even children could play.

This immediate verbal feedback on the success or failure of “defending my window” kept me both visually and mentally focused on the imaginary game I was playing, which, to my complete surprise, never failed to shift me out of the norm and into the zone. Even more surprising was that playing this same imaginary game shifted others into the zone as well; just as immediately and just as consistently. The fact that this process never failed so fascinated and intrigued me that I decided to study it from the inside by doing it, and from the outside by teaching it and reading as much as I could about it, understanding right from the start that there were some major differences in the way I was using my eyes that took me out of my normal performance state and put me into my peak performance state.

This change in visual dynamics was a change from focusing on the ball as it flew back and forth across the net, which is a Variable-Depth of Focus visual input pattern (VDF), to focusing on the contact zone and looking for the point the ball first enters the contact zone, which is a Fixed-Depth of Focus visual input pattern (FDF). (Ford, Hines, Kluka, 1998)

The act of visualizing an imaginary window in front of me acted to fix my visual and mental focus on my contact zone, and then by simply looking along the surface of this imaginary window for the point the ball contacted the window, I was effectively locating the Primary Contact Point – the point the ball first entered the space and time of my contact zone

This simple imaginary game that was getting everyone who tried it into their peak performance state obviously had some underlying reasons that caused players to immediately and consistently shift into the zone, but in 1978, there wasn’t much out there about playing in the zone, and nothing that defined exactly how to do it, so I started my own investigation the only way I knew how, and that was to make sense out of these different ways of using my eyes. One way, my old way, the traditional way of focusing on the ball (VDF), always kept me playing in the norm, but this new way of fixing my focus on the contact zone and locating the contact point (FDF), always shifted me and everyone else into the zone, and I wanted to know why. So I started with a diagram of the fundamental sequence in the game of tennis: the Contact Sequence.

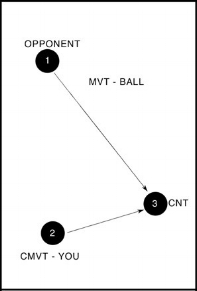

Any sport involving Movement, Countermovement, and Contact falls into the category of a Contact Sequence sport. Tennis fits nicely into that category. So do baseball, soccer, volleyball, lacrosse, and a host of other sports.

Any sport involving Movement, Countermovement, and Contact falls into the category of a Contact Sequence sport. Tennis fits nicely into that category. So do baseball, soccer, volleyball, lacrosse, and a host of other sports.

In tennis, every Contact Sequence begins with the Movement of the ball, followed by your Countermovement to intercept the ball, ending in Contact, the event that occurs when Movement and Countermovement come together at a common point in space and time – the Contact Point.

MVT --> CMVT --> CNT 1 --> 2 --> 3

If you look closely, you can see that this Contact Sequence is a map of the external reality of tennis. It also shows the external reality of every sport involving contact of any kind, which makes the Contact Sequence fundamental to athletic reality. It shows how you, as a sensorimotor system of countermovement, play an active role in the map itself. Not only are you a participant in the map; you are also the co-creator of the map. In other words, in every Contact Sequence you are a co-creator of your own performance reality; you are the map-maker.

This Contact Sequence map is important because it patterns a complete contact experience; it has a beginning, middle, and an end; an Alpha Point and an Omega Point, with the Omega Point of the old Contact Sequence being simultaneously the Alpha Point of the new Contact Sequence. Like Whitehead’s actual occasions, each Contact Sequence is a complete unit of experience that, at the moment of contact, comes to its conclusion as a fully unified field of experience. Every Contact Sequence also contains what Whitehead called the “the three notions that complete the Category of the Ultimate” Those notions are: the one, the many, and creativity. (Whitehead, 1978)

As you can see, each Contact Sequence has its own parts (the many), and those parts come together at contact to make a whole (the one), and at contact, something new is always created (creativity). The ultimate notions necessary for the creative advance into novelty all found in this fundamental map of athletic experience.

Look a little closer and you’ll notice that every Contact Sequence has both an absolute nature as well as a relative nature. The 1à2à3 sequence of MVTàCMVTàCNT is always the same. The absolute nature of every Contact Sequence is always already there prior to the arising of the Contact Sequence itself, and that absolute nature never changes.

But the relative nature of every Contact Sequence always changes. No two Contact Sequences are ever the same. Add to that the fact that every sport involving contact has its own individual look, its own rules, its own tools, its own athletic environment, and you can see how every Contact Sequence has a relative nature that arises with and within its absolute nature.

The more I investigated this simple Contact Sequence, the more interesting it became. Not only does every Contact Sequence involve the notions of the ultimate – the one, the many, and creativity – every Contact Sequence also contains both an absolute nature that never changes and a relative nature that always changes and evolves into something new and different. And finally, if you look even deeper, you’ll see that this map of the underlying reality of sport also contains something else, a hidden piece to the puzzle of human peak performance that is found in the temporal logic and spatial structure of every Contact Sequence.

Here’s the temporal logic: as the system of countermovement in every Contact Sequence, you, the athlete, are always occupying your present space. Physically, you are always “in the present.”

MVT --> CMVT --> CNT (Present)

Movement, however, occurs prior to your countermovement, before the present, “in the past.” So, relative to you, movement occurred in the past.

MVT --> CMVT -->CNT (Past) -->(Present)

However, relative to both the movement of the ball and your countermovement to intercept the ball, contact occurs last, after the past and present, “in the future.” So, relative to movement and countermovement, contact will occur in the future.

MVT --> CMVT --> CNT (Past)-->(Present)-->(Future)

This is the temporal logic of every Contact Sequence. This is always the way a Contact Sequence occurs in Time:

MVT --> CMVT --> CNT 1 --> 2 --> 3 Ball --> You--> Contact (Past) -->(Present)-->(Future)

But notice the difference in the spatial structure of every Contact Sequence. This is how every Contact Sequence occurs in Space:

MVT --> CNT <-- CMVT 1 --> 3 <-- 2 (Past)-->(Future)<--(Present) Ball --> Contact <-- You

Notice that the future of the Contact Sequence lies spatially between the past and the present. That holds true for every Contact Sequence whether it’s a tennis Contact Sequence, a baseball Contact Sequence, or a Contact Sequence in any other relationship involving a contact of any kind.

So every Contact Sequence contains its own temporal logic and spatial structure along with its own absolute and relative nature as well as reality’s ultimate categories – the one, the many, and creativity.

That’s a lot happening in one map, but what made this map so valuable to my own investigation of the zone was that it showed the difference between what I was focusing on when I focused on the ball versus what I was focusing on when I focused on my imaginary window.

I realized that when I focused on the ball, I was focusing on the past relative to my body in the present. So even though my body was physically in the present, my eyes and my mind were focused on the past. Granted, it was the immediate past relative to me in the present, but it was the past nonetheless. The logical conclusion was that when I was playing in my normal performance state, focusing on the ball, on form, on the objects of the material dimension of the Contact Sequence, I was playing “in the past.”

The human peak performance state is definitely not about playing in the past. One of the primary characteristics of flow reported by athletes from around the world is the sense of being “in the present.” Anyone who has ever been in the zone knows the feeling of total presence, the sense of being one with the game, one with the flow of the action, right here, right now.

That’s exactly how I felt every time I started defending my imaginary window with my racquet. And as I looked at what was actually happening according to this map of the spatiotemporal reality of sport, I saw the hidden piece to the puzzle of flow.

I realized that while I was visualizing this imaginary window in front of me, I was no longer focusing on the ball, no longer focusing on the past. Instead, I was focusing on my Contact Zone, focusing on the future depth of contact while, at the same time, as I looked for the contact point along the surface of my imaginary window, I was still “seeing” the past movement of the ball. In other words, when I used FDF as my visual input pattern, I was visually and mentally aware of the past and future dimensions of the Contact Sequence equally and simultaneously.

FDF was a visual input pattern in which I was using my eyes to input parallel streams of visual information to my brain about the past and the future of each arising Contact Sequence, and those parallel streams of past and future information combined to co-create the spatiotemporal dimension of the Present.

With that realization, everything about playing in the zone started to make sense. The underlying spatiotemporal dimension of flow is the present dimension, the flowing present, and by inputting parallel streams of visual information about the past and the future equally and simultaneously, the human operating system actively creates a parallel interface in which the past and the future are no longer separate dimensions. The past and the future are no longer two, but rather they combine to co-create the unified spatiotemporal reality of the flowing present. And with flowing presence, the underlying spatiotemporal reality of the human peak performance state is manifested.

This simple map of the Contact Sequence turned out to be a map of much more than just hitting a tennis ball or a baseball, or kicking soccer balls and spiking volleyballs. It was a map of the spatiotemporal relativity of a single athletic moment, a drop of athletic experience in Space and Time, a moment in which the parts come together to create a unified whole. This simple little diagram was a map of a unified temporal and spatial relativity field. I called them R-Fields for short, and every time your countermovements come together with the movement of any object in your environment, you create a contact event that brings one R-field to its end and starts another anew. The creative advance into novelty writ large in the smallest of Contact Sequences.

The Quadratic Structure of Performance States

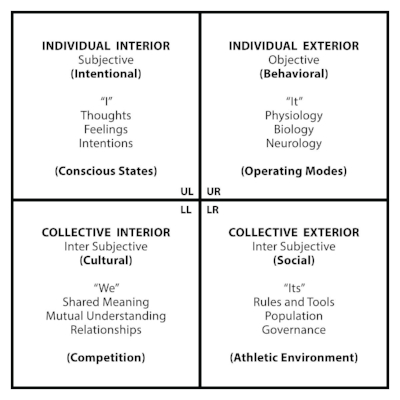

A major resource in my study of playing in the zone has been the body of work by Ken Wilber, one of the most influential philosophers and thinkers or our time. Wilber’s AQAL (All Quadrants - All Levels - All Lines - All States - All Types) map of reality divides all human experience, including sports experience, into four different perspectives. Here’s a quick run-down of the Wilber’s AQAL framework as it pertains to sport in general.

· The Upper-Left Quadrant. The Individual-Interior or “I” perspective that is intentional and subjective. My thoughts, feelings, values, motivations; the state of consciousness in which I play my sport.

· The Upper-Right Quadrant. The Individual-Exterior or “It” perspective that is behavioral and objective. My physical body, its biology, neurology, biomechanics; the mode of operation in which I play my sport.

· The Lower-Left Quadrant. The Collective-Interior or “We” perspective that is cultural and intersubjective. The values, language, mutual understanding, and relationships I share with others in the competitive culture of our sport.

· The Lower-Right Quadrant. The Collective-Exterior or “Its” perspective that is social and interobjective. The rules and tools of the particular sport; the athletic environment, its population of players, and, of importance to performance, my functional interface within the environment.

Applying Wilber’s AQAL model to sport, we can see that our individual performance experiences, both normal and peak, involve a relationship between interior consciousness (UL quadrant), exterior operation (UR quadrant), the functional interface of the athlete within the exterior environment (LR quadrant), and the shared interior values of the competition (LL quadrant),

Every time we step into the environment of competition, these four perspectives are always present, providing us with the underlying structure of performance. But, as you will see, the underlying structure of our peak performance state is dramatically different from the underlying structure of our normal performance state. Our different performance experiences have different quadratic dynamics, different interior and exterior correlates that co-create the performance experience itself.

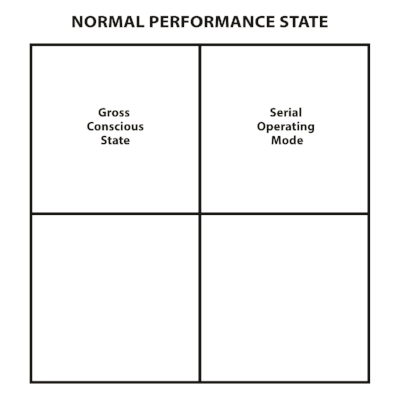

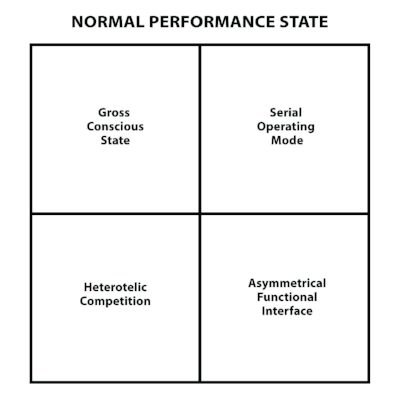

For example: we’re all familiar with our normal performance state and the normal state of consciousness that accompanies it. This normal state of consciousness is known as Gross Consciousness, and this gross interior state has a corresponding exterior correlate – a Serial Mode of operation, which is also our normal mode of operation whether we’re playing baseball, basketball, football, tennis, hockey, or jogging in the park.

The UL and UR quadrants of our normal performance state looks like this:

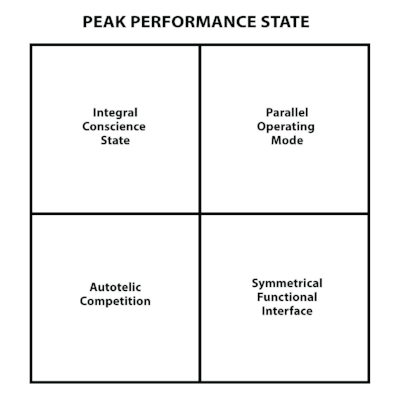

Our peak performance state also has its own look in the UL and UR quadrants, but it involves a completely different interior state of consciousness – a state of Integral Consciousness, along with a completely different exterior correlate, a Parallel Mode of operation, which is our most efficient and accurate mode of sensorimotor operation.

In short, our peak performance state is radically different from our normal performance state in the UL and UR quadrants, which look like this:

The simultaneity of these interior and exterior correlates means that if we create one correlate we simultaneously create the other, and that gives us two very different options for creating our peak performance state:

Option #1: We can create its interior state – a state of integral consciousness – and, in so doing, simultaneously create its exterior correlate – a Parallel Mode of operation.

Or

Option #2: We can create its exterior mode of operation – a Parallel Mode – and, in so doing, simultaneously create its interior correlate – a state of integral consciousness.

In the summer of 1978, without knowing it, I accidentally stumbled across Option #2.

The childlike game I started playing in which I used my tennis racquet to keep every ball from getting past my imaginary window was, in fact, a game that caused me to shift out of a Serial Mode of operation and into a Parallel Mode of operation – the exterior mode of operation whose simultaneous interior correlate is a state of integral consciousness.

In other words, I accidentally stumbled across this:

When I stopped using my racquet to hit every ball over the net and started using my racquet to prevent every ball from getting past my imaginary window, I was intentionally creating the performance structure seen in Option #2. I was intentionally creating the specific exterior state of peak performance – a Parallel Mode of operation – and, in so doing; I was simultaneously creating its interior correlate – a state of integral consciousness.

End result: immediate access to the unified reality of the human peak performance state. Immediate access to the zone.

***

But sport does not take place in a vacuum, so the lower quadrants must also be included to fully map out these radically different performance states. The difference in the quadratic dynamics of the lower right quadrant is seen when you compare the functional interface co-created by athletes performing in their Serial Mode of operation versus athletes performing in the Parallel Mode of operation.

When athletes enter into the athletic environment of their sport, they can enter that environment in either their Serial Mode of operation with its interior state of gross consciousness or their Parallel Mode of operation with its interior state of integral consciousness. Both of these performance structures act to co-create a functional interface between the athlete’s operating system and the spatiotemporal environment in which it is operating.

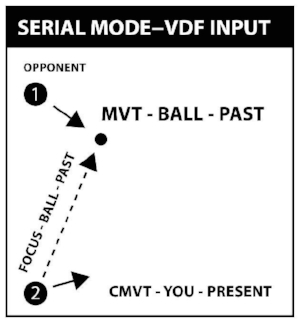

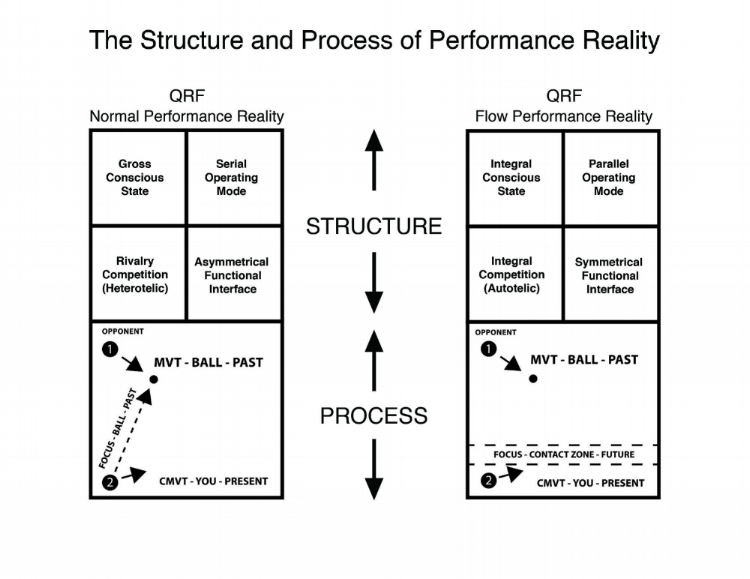

One functional interface – that of the Serial Mode of operation – is asymmetrical in that it involves the sensorimotor operating system connecting to only the past dimension of form while ignoring the future dimension of empty space. This is seen when athletes focus on the ball or their opponent – the past dimension of form – while ignoring the future dimension of their contact zone (empty space). An interface that is connected to only half of the available spatiotemporal information in the R-field environment is an asymmetrical functional interface, and that’s what you co-create when you enter the athletic environment in your Serial Mode of operation.

The second functional interface – that of the Parallel Mode of operation – is symmetrical in that it involves the sensorimotor operating system connecting to the past dimension of form (ball) and the future dimension of the contact zone (empty space). An interface that is connected equally and simultaneously to the past and future spatiotemporal dimensions of the arising R-field environment is a symmetrical functional interface, and that’s what you co-create when you enter the athletic environment in your Parallel Mode of operation.

In our map of the different performance states, the upper quadrants and the lower right quadrants look like this:

Athletes don’t play better because they are in the zone. They play better because when they are in this state of integral consciousness with its Parallel Mode of exterior operation they are connected to the athletic R-field environment in their most efficient, accurate, and fully-potentiated functional interface – a symmetrical functional interface. And this symmetrical functional interface creates a one-to-one connection between athlete and action; a one-to-one connection that is causal to the higher level of performance athletes experience when they are in the zone.

The different functional interfaces found in the Lower Right quadrants of these dramatically different performance states can best be seen in their R-field dynamics:

These R-field maps are maps of the functional interface that occurs in the LR quadrant of our normal and peak performance states. One map shows you how to use your visual and mental focus to connect to only half of the available spatiotemporal information in the R-field, thus co-creating a partially-potentiated, asymmetrical functional interface. The other map shows you how to use your visual and mental focus to connect to all of the spatiotemporal information in the same R-field, thus co-creating a fully-potentiated, symmetrical functional interface. In short, these are maps that show you “how to do it.”

The LR quadrant, the interobjective quadrant in which the sensorimotor operating system manifests its functional interface, be it asymmetrical or symmetrical. Humans are capable of either interface no matter what their level of skill, no matter their age, gender, or race. The fact that they are human and have a sensorimotor operating system means that they have a choice in how they use that operating system to connect to the fast-moving, problem-solving, decision-making, relational environment of any Contact Sequence sport or any Contact Sequence relationship.

The exterior, interobjective quadrant (LR) also has a correlative interior, intersubjective quadrant(LL). Where the exterior of the sport involves the athletic environment, its rules and tools, its governance, its population of players as well as the athlete’s functional fit within the environment, the interior of the sport involves a mutual understanding of the competition, the relational “we-space” in which the shared meaning of the competition differs according to the interior state of consciousness the athlete brings to that competitive we-space.

***

Athletes who have experienced competition in their peak performance state consistently report on a different sense of the competition itself. No longer is their sense of competition the same as that of their normal performance state. Athletes in their normal performance state have a sense of competing against their opponent(s) in order to gain some extrinsic reward, such as winning, or trophies, money, power, or prestige. But athletes who compete in their peak performance state have a sense of competing with their opponent(s) in order to gain some intrinsic reward, such as enjoyment, personal development, self-actualization, even self-transcendence. Competing for an extrinsic reward (winning) is called “heterotelic” or rivalry competition, while competing for an intrinsic reward (development) is called “autotelic” or integral competition.

Just as there is a significant difference between an asymmetrical functional interface and a symmetrical functional interface in the R-field environment of the lower right quadrant, there is also a significant difference between a heterotelic experience and an autotelic experience in the competitive culture of the lower left quadrant.

With these lower quadrant perspectives in place, all four quadrants of both performance states can be seen like this:

And when you include the R-field diagrams of both performance states, you get a complete map of the QRF dynamics of both the human normal performance state and the human peak performance state:

The quadrants define the different interior and exterior dynamics of these two opposing performance states, while their corresponding R-field dynamics define exactly how to co-create the spatiotemporal dimension of the flowing present, and with the co-creation of flowing presence you get peak performance – by choice and not by chance. The human peak performance state is a flow state, and that flow state is a state in which your sensorimotor operating system is in a one-to-one interface with the flowing present dimension of each R-field moment; moment to moment to moment. You can attempt to enter the peak performance state in different ways, but one way to guarantee immediate access to a flow state is to co-create its underlying spatiotemporal dimension – the flowing present.

Conclusions

QRF dynamics provide a framework in which the interior and exterior dynamics of the individual athlete can be measured relative to the interior and exterior dynamics of their respective sports in both their normal and peak performance states. The differences between the QRF dynamics of the normal performance state and the QRF dynamics of the peak performance state show how these two performance states stand in radical opposition to each other.

Summary of the Quadrant opposition between the normal and the peak performance states:

Gross Consciousness vs. Integral Consciousness in the Upper Left Quadrant. Serial Operation vs. Parallel Operation in the Upper Right Quadrant. Asymmetrical Functionality vs. Symmetrical Functionality in the Lower Right Quadrant. Heterotelic (Rivalry) Competition vs. Autotelic (Integral) Competition in the Lower Left Quadrant.

Summary of the R-field opposition between the normal and peak performance states:

NPS: Asymmetrical Functional Interface – serial input of past dimension only/future ignored. Playing “in the past.”

PPS: Symmetrical Functional Interface – parallel input of past and future dimensions equally and simultaneously, co-creating the flowing present. Playing “in the present.”

So QRF dynamics can be used to not only model the interior and exterior correlates of both performance states, but with the inclusion of R-field dynamics, coaches and athletes alike are shown exactly how to co-create these different performance states via the co-creation of their underlying spatiotemporal relativity fields.

Earlier performance models stop at the zone, with conventional wisdom insisting that a flow state cannot be manufactured intentionally. But emerging performance models, such as QRF Dynamics, begin with the zone, and by redefining the structure and process of the peak performance state, performance models of the future will not only include the positive training practices of classic performance models, but will also add the higher-consciousness and sensorimotor training of today’s emerging performance models.

Bibliography

Websites:

Whitehead, A. N. (1978). Process and Reality. New York: Free Press.

Ford, S., Hines, William, Kluka, D. (1998). International Journal of Volleyball Research, Vol. 3, No. 1